Electric cars don’t solve the automobile’s environmental problems

Last summer, California highway police pulled over pop star Justin Bieber as he sped through Los Angeles in an attempt to shake the paparazzi. He was driving a hybrid electric car—not just any hybrid, mind you, but a chrome-plated Fisker Karma, a US $100 000 plug-in hybrid sports sedan he’d received as an 18th-birthday gift from his manager, Scooter Braun, and fellow singer Usher. During an on-camera surprise presentation, Braun remarked, “We wanted to make sure, since you love cars, that when you are on the road you are always looking environmentally friendly, and we decided to get you a car that would make you stand out a little bit.” Mission accomplished.

Bieber joins a growing list of celebrities, environmentalists, and politicians who are leveraging electric cars into green credentials. President Obama once dared to envision 1 million electric cars plying U.S. roads by 2015. London’s mayor, Boris Johnson, vibrated to the press over his born-again electric conversion after driving a Tesla Roadster, marveling how the American sports coupe produced “no more noxious vapours than a dandelion in an alpine meadow.” Meanwhile, environmentalists who once stood entirely against the proliferation of automobiles now champion subsidies for companies selling electric cars and tax credits for people buying them.

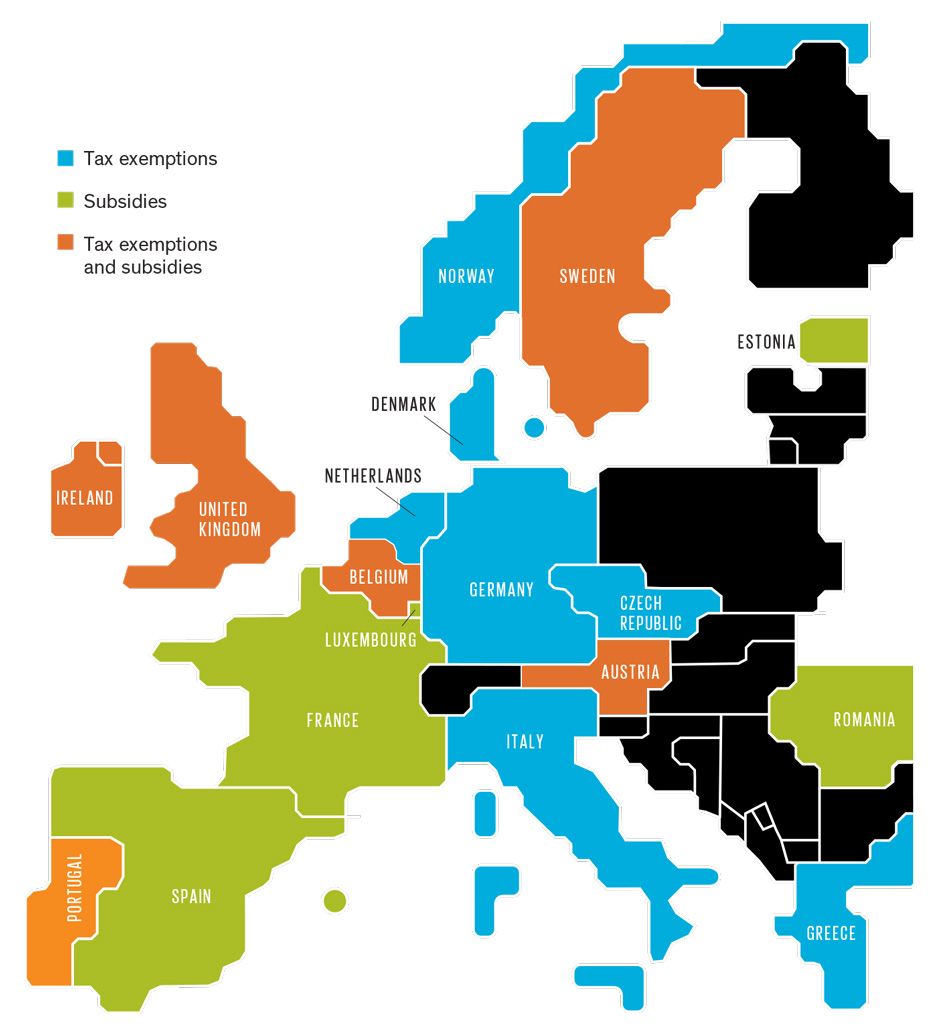

Two dozen governments around the world subsidize the purchase of electric vehicles. In Canada, for example, the governments of Ontario and Quebec pay drivers up to C $8500 to drive an electric car. The United Kingdom offers a £5000 Plug-in Car Grant. And the U.S. federal government provides up to $7500 in tax credits for people who buy plug-in electric vehicles, even though many of them are affluent enough not to need such help. (The average Chevy Volt owner, for example, has an income of $170 000 per year.)

Some states offer additional tax incentives. California brings the total credit up to $10 000, and Colorado to $13 500—more than the base price of a brand new Ford Fiesta. West Virginia offers the sweetest deal. The state’s mining interests are salivating at the possibility of shifting automotive transportation from petroleum over to coal. Residents can receive a total credit of up to $15 000 for an electric-car purchase and up to $10 000 toward the cost of a personal charging station.

There are other perks. Ten U.S. states open the high-occupancy lanes of their highways to electric cars, even if the car carries a lone driver. Numerous stores offer VIP parking for electric vehicles—and sometimes a free fill-up of electrons. Mayor Johnson even moved to relieve electric-car owners of the burden of London’s famed congestion fee.

Alas, these carrots can’t overcome the reality that the prices of electric cars are still very high—a reflection of the substantial material and fossil-fuel costs that accrue to the companies constructing them. And some taxpayers understandably feel cheated that these subsidies tend to go to the very rich. Amid all the hype and hyperbole, it’s time to look behind the curtain. Are electric cars really so green?

The idea of electrifying automobiles to get around their environmental shortcomings isn’t new. Twenty years ago, I myself built a hybrid electric car that could be plugged in or run on natural gas. It wasn’t very fast, and I’m pretty sure it wasn’t safe. But I was convinced that cars like mine would help reduce both pollution and fossil-fuel dependence.

I was wrong.

I’ve come to this conclusion after many years of studying environmental issues more deeply and taking note of some important questions we need to ask ourselves as concerned citizens. Mine is an unpopular stance, to be sure. The suggestive power of electric cars is a persuasive force—so persuasive that answering the seemingly simple question “Are electric cars indeed green?” quickly gets complicated.

As with most anything else, the answer depends on whom you ask. Dozens of think tanks and scientific organizations have ventured conclusions about the environmental friendliness of electric vehicles. Most are supportive, but a few are critical. For instance, Richard Pike of the Royal Society of Chemistry provocatively determined that electric cars, if widely adopted, stood to lower Britain’s carbon dioxide emissions by just 2 percent, given the U.K.’s electricity sources. Last year, a U.S. Congressional Budget Office study found that electric car subsidies “will result in little or no reduction in the total gasoline use and greenhouse-gas emissions of the nation’s vehicle fleet over the next several years.”

Others are more supportive, including the Union of Concerned Scientists. Its 2012 report [PDF] on the issue, titled “State of Charge,” notes that charging electric cars yields less CO2 than even the most efficient gasoline vehicles. The report’s senior editor, engineer Don Anair, concludes: “We are at a good point to clean up the grid and move to electric vehicles.”

Why is the assessment so mixed? Ultimately, it’s because this is not just about science. It’s about values, which inevitably shape what questions the researchers ask as well as what they choose to count and what they don’t. That’s true for many kinds of research, of course, but for electric cars, bias abounds, although it’s often not obvious to the casual observer.

To get a sense of how biases creep in, first follow the money. Most academic programs carrying out electric-car research receive funding from the auto industry. For instance, the Plug-in Hybrid and Electric Vehicle Research Center at the University of California, Davis, which describes itself as the “hub of collaboration and research on plug-in hybrid and electric vehicles for the State of California,” acknowledges on its website partnerships with BMW, Chrysler-Fiat, and Nissan, all of which are selling or developing electric and hybrid models. Stanford’s Global Climate & Energy Project, which publishes research on electric vehicles, has received more than $113 million from four firms: ExxonMobil, General Electric, Schlumberger, and Toyota. Georgetown University, MIT, the universities of Colorado, Delaware, and Michigan, and numerous other schools also accept corporate sponsorship for their electric-vehicle research.

I’m not suggesting that corporate sponsorship automatically leads people to massage their research data. But it can shape findings in more subtle ways. For one, it influences which studies get done and therefore which ones eventually receive media attention. After all, companies direct money to researchers who are asking the kinds of questions that stand to benefit their industry. An academic who is studying, say, car-free communities is less likely to receive corporate funding than a colleague who is engineering vehicle-charging stations.

Many of the researchers crafting electric-vehicle studies are eager proponents of the technology. An electric-vehicle report from Indiana University’s School of Environmental Affairs, for instance, was led by a former vice president of Ford. It reads like a set of public relations talking points and contains advertising recommendations for the electric-car industry (that it should manage customers’ expectations, to avoid a backlash from excessive claims). Even the esteemed Union of Concerned Scientists clad its electric-car report in romantic marketing imagery courtesy of Ford, General Motors, and Nissan, companies whose products it evaluates. Indeed, it’s very difficult to find researchers who are looking at the environmental merits of electric cars with a disinterested eye.

So how do you gauge the environmental effects of electric cars when the experts writing about them all seem to be unquestioned car enthusiasts? It’s tough. Another impediment to evaluating electric cars is that it’s difficult to compare the various vehicle-fueling options. It’s relatively easy to calculate the amount of energy required to charge a vehicle’s battery. It isn’t so straightforward, however, to compare a battery that’s been charged by electricity from a natural-gas-fired power plant with one that’s been charged using nuclear power. Natural gas requires burning, it produces CO2, and it often demands environmentally problematic methods to release it from the ground. Nuclear power yields hard-to-store wastes as well as proliferation and fallout risks. There’s no clear-cut way to compare those impacts. Focusing only on greenhouse gases, however important, misses much of the picture.

Manufacturers and marketing agencies exploit the fact that every power source carries its own unique portfolio of side effects to create the terms of discussion that best suit their needs. Electric-car makers like to point out, for instance, that their vehicles can be charged from renewable sources, such as solar energy. Even if that were possible to do on a large scale, manufacturing the vast number of photovoltaic cells required would have venomous side effects. Solar cells contain heavy metals, and their manufacturing releases greenhouse gases such as sulfur hexafluoride, which has 23 000 times as much global warming potential as CO2, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. What’s more, fossil fuels are burned in the extraction of the raw materials needed to make solar cells and wind turbines—and for their fabrication, assembly, and maintenance. The same is true for the redundant backup power plants they require. And even more fossil fuel is burned when all this equipment is decommissioned. Electric-car proponents eagerly embrace renewable energy as a scheme to power their machines, but they conveniently ignore the associated environmental repercussions.

Finally, most electric-car assessments analyze only the charging of the car. This is an important factor indeed. But a more rigorous analysis would consider the environmental impacts over the vehicle’s entire life cycle, from its construction through its operation and on to its eventual retirement at the junkyard.

One study attempted to paint a complete picture. Published by the National Academies in 2010 and overseen by two dozen of the United States’ leading scientists, it is perhaps the most comprehensive account of electric-car effects to date. Its findings are sobering.

It’s worth noting that this investigation was commissioned by the U.S. Congress and therefore funded entirely with public, not corporate, money. As with many earlier studies, it found that operating an electric car was less damaging than refueling a gasoline-powered one. It isn’t that simple, however, according to Maureen Cropper, the report committee’s vice chair and a professor of economics at the University of Maryland. “Whether we are talking about a conventional gasoline-powered automobile, an electric vehicle, or a hybrid, most of the damages are actually coming from stages other than just the driving of the vehicle,” she points out.

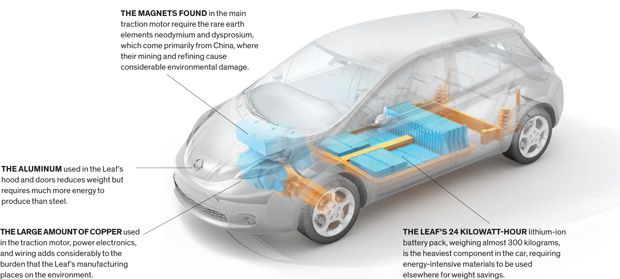

Part of the impact arises from manufacturing. Because battery packs are heavy (the battery accounts for more than a third of the weight of the Tesla Roadster, for example), manufacturers work to lighten the rest of the vehicle. As a result, electric car components contain many lightweight materials that are energy intensive to produce and process—carbon composites and aluminum in particular. Electric motors and batteries add to the energy of electric-car manufacture.

In addition, the magnets in the motors of some electric vehicles contain rare earth metals. Curiously, these metals are not as rare as their name might suggest. They are, however, sprinkled thinly across the globe, making their extraction uneconomical in most places. In a study released last year, a group of MIT researchers calculated that global mining of two rare earth metals, neodymium and dysprosium, would need to increase 700 percent and 2600 percent, respectively, over the next 25 years to keep pace with various green-tech plans. Complicating matters is the fact that China, the world’s leading producer of rare earths, has been attempting to restrict its exports of late. Substitute strategies exist, but deploying them introduces trade-offs in efficiency or cost.

The materials used in batteries are no less burdensome to the environment, the MIT study noted. Compounds such as lithium, copper, and nickel must be coaxed from the earth and processed in ways that demand energy and can release toxic wastes. And in regions with poor regulations, mineral extraction can extend risks beyond just the workers directly involved. Surrounding populations may be exposed to toxic substances through air and groundwater contamination.

At the end of their useful lives, batteries can also pose a problem. If recycled properly, the compounds are rather benign—although not something you’d want to spread on a bagel. But handled improperly, disposed batteries can release toxic chemicals. Such factors are difficult to measure, though, which is why they are often left out of studies on electric-car impacts.

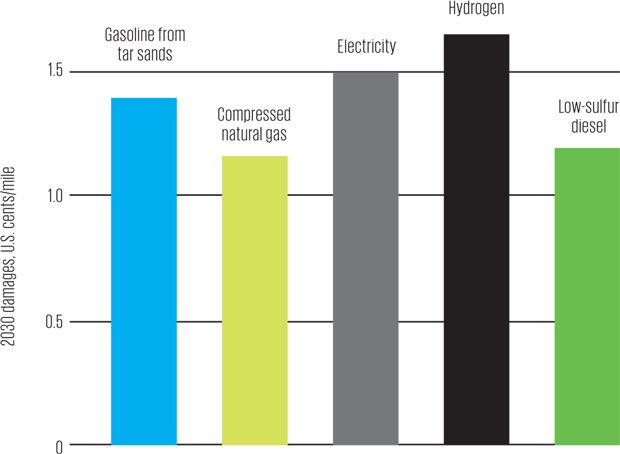

The National Academies’ assessment didn’t ignore those difficult-to-measure realities. It drew together the effects of vehicle construction, fuel extraction, refining, emissions, and other factors. In a gut punch to electric-car advocates, it concluded that the vehicles’ lifetime health and environmental damages (excluding long-term climatic effects) are actually greater than those of gasoline-powered cars. Indeed, the study found that an electric car is likely worse than a car fueled exclusively by gasoline derived from Canadian tar sands!

As for greenhouse-gas emissions and their influence on future climate, the researchers didn’t ignore those either. The investigators, like many others who have probed this issue, found that electric vehicles generally produce fewer of these emissions than their gasoline- or diesel-fueled counterparts—but only marginally so when full life-cycle effects are accounted for. The lifetime difference in greenhouse-gas emissions between vehicles powered by batteries and those powered by low-sulfur diesel, for example, was hardly discernible.

The National Academies’ study stood out for its comprehensiveness, but it’s not the only one to make such grim assessments. A Norwegian study published last October in the Journal of Industrial Ecology compared life-cycle impacts of electric vehicles. The researchers considered acid rain, airborne particulates, water pollution, smog, and toxicity to humans, as well as depletion of fossil fuel and mineral resources. According to coauthor Anders Stromman, “electric vehicles consistently perform worse or on par with modern internal combustion engine vehicles, despite virtually zero direct emissions during operation.”

Earlier last year, investigators from the University of Tennessee studied five vehicle types in 34 Chinese cities and came to a similar conclusion. These researchers focused on health impacts from emissions and particulate matter such as airborne acids, organic chemicals, metals, and dust particles. For a conventional vehicle, these are worst in urban areas, whereas the emissions associated with electric vehicles are concentrated in the less populated regions surrounding China’s mostly coal-fired power stations. Even when this difference of exposure was taken into account, however, the total negative health consequences of electric vehicles in China exceeded those of conventional vehicles.

North American power station emissions also largely occur outside of urban areas, as do the damaging consequences of nuclear- and fossil-fuel extraction. And that leads to some critical questions. Do electric cars simply move pollution from upper-middle-class communities in Beverly Hills and Virginia Beach to poor communities in the backwaters of West Virginia and the nation’s industrial exurbs? Are electric cars a sleight of hand that allows peace of mind for those who are already comfortable at the expense of intensifying asthma, heart problems, and radiation risks among the poor and politically disconnected?

The hope, of course, is that electric-car technology and power grids will improve and become cleaner over time. Modern electric-car technology is still quite young, so it should get much better. But don’t expect batteries, solar cells, and other clean-energy technologies to ride a Moore’s Law–like curve of exponential development. Rather, they’ll experience asymptotic growth toward some ultimate efficiency ceiling. When the National Academies researchers projected technology advancements and improvement to the U.S. electrical grid out to 2030, they still found no benefit to driving an electric vehicle.

If those estimates are correct, the sorcery surrounding electric cars stands to worsen public health and the environment rather than the intended opposite. But even if the researchers are wrong, there is a more fundamental illusion at work on the electric-car stage.

All of the aforementioned studies compare electric vehicles with petroleum-powered ones. In doing so, their findings draw attention away from the broad array of transportation options available—such as walking, bicycling, and using mass transit.

There’s no doubt that gasoline- and diesel-fueled cars are expensive and dirty. Road accidents kill tens of thousands of people annually in the United States alone and injure countless more. Using these kinds of vehicles as a standard against which to judge another technology sets a remarkably low bar. Even if electric cars someday clear that bar, how will they stack up against other alternatives?

For instance, if policymakers wish to reduce urban smog, they might note that vehicle pollution follows the Pareto principle, or 80-20 rule. Some 80 percent of tailpipe pollutants flow from just 20 percent of vehicles on the road—those with incomplete combustion. Using engineering and remote monitoring stations, communities could identify those cars and force them into the shop. That would be far less expensive and more effective than subsidizing a fleet of electric cars.

If legislators truly wish to reduce fossil-fuel dependence, they could prioritize the transition to pedestrian- and bike-friendly neighborhoods. That won’t be easy everywhere—even less so where the focus is on electric cars. Studies from the National Academies point to better land-use planning to reduce suburban sprawl and, most important, fuel taxes to reduce petroleum dependence. Following that prescription would solve many problems that a proliferation of electric cars could not begin to address—including automotive injuries, deaths, and the frustrations of being stuck in traffic.

Upon closer consideration, moving from petroleum-fueled vehicles to electric cars begins to look more and more like shifting from one brand of cigarettes to another. We wouldn’t expect doctors to endorse such a thing. Should environmentally minded people really revere electric cars? Perhaps we should look beyond the shiny gadgets now being offered and revisit some less sexy but potent options—smog reduction, bike lanes, energy taxes, and land-use changes to start. Let’s not be seduced by high-tech illusions.

This article originally appeared in print as “Unclean at Any Speed.”