Address to the Commission’s 2010 Consultation on Energy

by Luis de Sousa

Sat Jul 3rd, 2010 at 01:52:22 PM EST

Below the fold can be found the submission I produced for the Commission’s Consultation on Energy. Time has been in short supply lately, what was initially conceived as a draft to be posted for public review and completion ended up successively postponed to the last few days. This version was sent to the Consultation’s e-mail box last night at 23H53 CET, only 7 minutes before the deadline. References are scant, some sections are incomplete and the English shaky here and there; but it contains some food for though, especially in the opening stages. [UPDATE 05-07-2010] A bunch of typos identified by melo corrected.

Below the fold can be found the submission I produced for the Commission’s Consultation on Energy. Time has been in short supply lately, what was initially conceived as a draft to be posted for public review and completion ended up successively postponed to the last few days. This version was sent to the Consultation’s e-mail box last night at 23H53 CET, only 7 minutes before the deadline. References are scant, some sections are incomplete and the English shaky here and there; but it contains some food for though, especially in the opening stages. [UPDATE 05-07-2010] A bunch of typos identified by melo corrected.

Address to the Commission’s 2010 Consultation on Energy

Luís Moreira de Sousa

luis.a.de.sousa@gmail.com

July 3, 2010

1 Introduction

This document is an attempt to address the Energy Consultation launched by the European Commission in the first half of 2010. This consultation is part of a process that shall take the Commission to a new Energy Policy Programme a few years from now.

After 6 years with energy prices much above the ground flat figures that made the norm during the previous two decades, the European Union is finally taking into due consideration this crucial sector. It is now contemplating an Economy highly dependent on foreign energy, together with meagre and dwindling traditional sources of indigenous energy. As it stands now, the Socio-Economic model the European Union is built on simply doesn’t seem able to perdure on traditional sources of energy, especially fossil fuels. This has lead to the Programme know as 20-20-20, that among other things, aims at increasing energy production from renewable energy sources and efficiency. This Programme is rather shy in many areas and in others it contradicts itself or is contradicted by other Communitarian policies.

It is more that time for a new, serious and all-encompassing Energy Policy for Europe. Otherwise the survival of Europe itself is at stake; and not only the European Construction project, but states themselves may disintegrate if they are not willing or capable of tackling the transition due ahead. Simply put, there’s no Economy without accessible and secure Energy, and without an Economy there’s no Social State.

This document is divided into two sections, one outlining the Background, where Europe is squared in today’s world energy market, and a second presenting a possible Policy, congruent with the given panorama, establishing goals and pointing possible means.

Some deeper issues that are either closely related to, or at the root of, today’s energy problems are not address in this document; two obvious cases are Population and the Monetary System. Essentially, the Policy presented assumes implicitly that Economic Growth is viable in the future. The aim of this document is to present practical options that can be easily grasped by lawmakers and stakeholders in general, leaving outside more complex concerns, that though important, should be discussed in a different context.

2 Background

This section tries to explain why energy come back to be a public concern in recent years and why stakeholders have been dedicated to it more than usual. Each fossil fuel is briefly analysed separately, with a few observations on the expected evolution of its availability. Finally, some reflections are made on the consequences to Europe’s Economy.

2.1 Oil

Oil prices began in 2004 a cavalcade that would last for almost 4 years, slowly breaking all previous records. Even in the wake of the hardest Economic recession of the last 30 years, oil prices are today about four times what they where a decade ago. These incessant high prices have lent the due credibility to those that for some time had warned against impeding difficulties in continuing the breathless world Oil production growth of the past two decades. Among these can be highlighted Colin Campbell and Jean Laherrére [1], Richard Duncan and Walter Youngquist [2] or Kenneth Deffeyes [3] for their oil production forecasts or Ali Bakhtiari [4] for his price predictions.

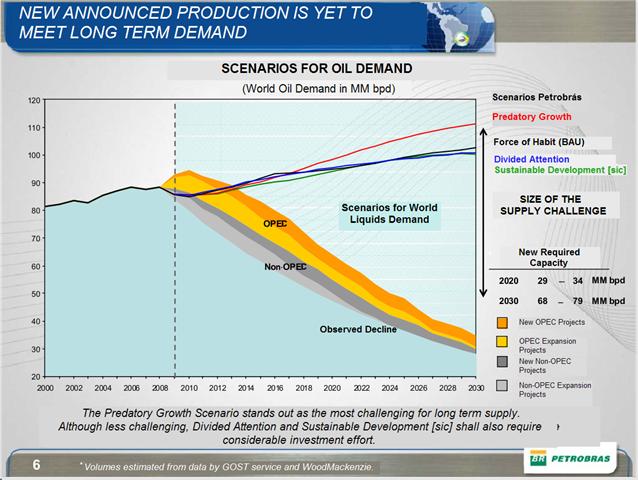

The constraints to oil production growth have today been acknowledge by most, even by the Industry itself [5], as show by Figure 1. Also notable have been the implicit warnings issued by the IEA, that despite continuously publishing production scenarios perpetually matching demand, have been vocal in other contexts explaining how unlikely that is to happen, especially in the figure of it’s Chief-Economist, Fatih Birol [6].

Peak Oil, as was baptised by Colin Campbell, is a pretty palpable reality at this stage, but for Europe reality is bit more intricate. Only one of its states is a net oil exporter, with most meeting their needs fully with imports. Figure 2 presents the volumes of oil made available at the international market every year by all the relevant exporters and a forecast of its evolution into the future. International oil trade peaked in 2005 and has entered a permanent decline; moreover, this decline will likely accelerate during the next decade, by 2020 taking away between 1/3 or 1/4 of the volume of oil available in the market in 2005. This has been the main reason behind the high price environment of the past 6 years.

But Europe’s woes deepen further, its most important suppliers, Norway and Russia, that supply Europe almost exclusively, are themselves entering terminal production decline. Within a decade Norway’s oil exports shall be no more that a small fraction of what they are today; as for Russia an halving of exports in the same period must be seen as likely.

It is hard to envision how Europe will square in this race for the dwindling international oil market. One thing is for certain, with its heavy foreign dependence and now diminutive internal production it is the Economic block with most to lose.

2.2 Gas

A Peak of world Natural Gas production is not something to expect in the short term. Though some have pointed to such possibility, even independent researchers usually position it some decades away. Today, with the development of unconventional reserves in North America, terminal decline in that region at least has been postponed for some years.

But Gas is not a fungible commodity like Oil, its trade is mostly regional, reliant on pipeline deliveries. Europe’s access to this energy source must be observed at a geographically restricted scope. Imports equate to about 60% of consumption, supplied by three neighbouring blocks: Russia, Norway and the Magreb. Norway is reaching its production zenith by now, with a visible reduction in exports unfolding in the next decade. Russia is still away from such decline, likely maintaining present production levels during the next fifteen to twenty years; the question on Russia is its internal demand, which has been slowly eating away export capacity. A maintenance of present Russian gas exports to Europe can be seen as a best case scenario. The only export capacity growth to expect is from the Magreb, though not in sufficient volumes to make the gap opened by the other two neighbouring suppliers.

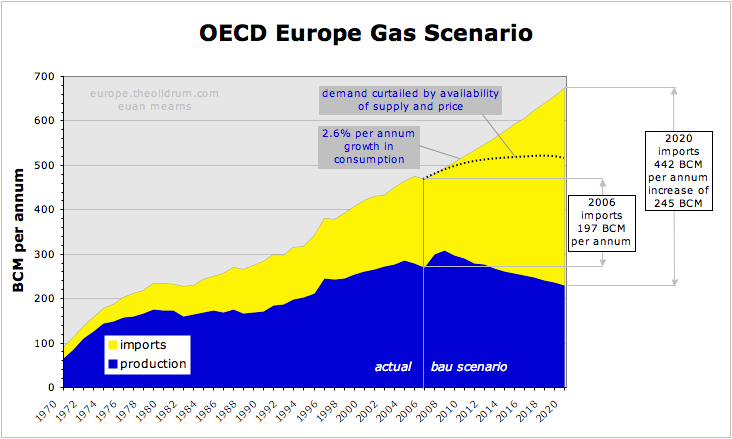

Compounding on this imports scenario is a declining internal production. Peaking in 2001 during the golden days of the North Sea, gas production in Europe has been slowly declining up to now and should accelerate into the future. A huge gap will open between production and a relentless demand that up to 2008 had been growing 2% annually. Euan Mearns [8] produced an analysis of the European Gas Market in 2007 that detailed these issues, a digest is presented in Figure 3. The only way to match an annual demand growth of 2% would be importing all the Natural Gas traded in the world by ship in liquid state. The likelihood of that is very slim, especially in face of competition from emerging economies.

In Europe, but especially in the United States, Natural Gas has been used as a campaigning flag by some politicians, promoting it as a benign or beneficial energy source, in some cases even casting the idea of a non-fossil origin [9]. This has created the wrong impression that Gas may be the answer to most, if not all, of the world’s energy problems. The United Kingdom, for instance, is expecting to be generating two thirds of its electricity from Natural Gas a few years from now; how that will be possible is beyond anyone.

2.3 Coal

Like Gas, a peak of world Coal production is not to be expected in the short term. And unlike the two previous fossil fuels, reserves and future production profiles estimates are yet to converge. Predictions exist for a world Coal Peak between 2025 and 2060, remaining open the question of whether it can ever surpass today’s energy flow from Oil.

In the short term Coal presents different challenges, stemming from the relatively small size of its international market; most of the Coal mined in the world is consumed within borders. Coal consumption in the EU has decreased dramatically in the wake of the economic crisis (down 17% since 2008) but it still is the main source of baseload electricity in most states, with 45% of it being imported. On the other side of the table are the emerging economies, India alone should in 2010 consume more Coal than the EU for the first time in History; as for China, it consumes almost half of all the Coal mined in the world, almost six times what the EU consumes and growing close to 10% per annum.

So far China remained Coal self-sufficient, despite some sporadic periods when it had to temporarily recur to the international market. One of these episodes took place in the Spring of 2007, at a time when prices in Europe where around 45 $/tonne. China became a net importer of Coal for a few months and even after closing the gap later that year, faced a harsh Winter in the early weeks of 2008, that compromised mining and transport, prompting shortages in most of the country. By this time Coal was being traded at the Amsterdam port for more than 140 $/tonne [10]. It took less than 12 months for Coal prices to produce the same move Oil prices made in four years.

Coal Consumption in Asia is growing so fast that episodes like the 2007/2008 crunch can become permanent. The IEA expects China and India together to be demanding over 110 Mtoe on the international market already by 2015 [6]; this figure is very close to what the EU imported together in 2009. Can the international market cope with such demand surge? Of all international fossil fuel markets, Coal may well be the one yielding the greatest surprises for the next decade.

2.4 Fossil Fuels and the Economy

High energy prices had been the omens of Economic Recession during the XX century, once it became clear in 2004 that OPEC was impotent to rein in oil prices, many where those announcing an imminent crisis. The shock came only in 2008, when high energy prices coupled with rising interest rates dried up household spending and triggered credit defaults throughout much of the OECD. This crisis revealed serious fragilities in the financial system with over indebtedness by households, companies and states.

In Europe this recession had different impacts on different states, but immediately threatened liquidity all across the bloc. This was dealt at the time with state guarantees on private bank credit, but with economic activity nearly stalled, it evolved into a confidence crisis on state solvability. This confidence crisis affected only some states, particularly those in the Eurogroup with large budget deficits, though they are indebted mostly to other EU states. But it is paramount to note that those states that are today in bigger trouble to finance themselves are exactly those more reliant on Oil as primary energy source [11], as Figure 4 shows.

There may be several reasons for this coincidence, but it clearly shows that fossil fuel dependence is having a determining role in the present crisis. Moreover, it also indicates that a Pan-European scope is indispensable for an effective Energy Policy.

The Economic Crisis is now going on for almost 2 years. GDP numbers may have grown occasionally, but Unemployment figures are still high and in some cases still growing. At the same time oil prices remain about 2.5 times what they where back in 2004. An Economy based on fossil fuels will always have little roam to grow while supplies of these energy sources remai